by Becca Levy and Jared Rubin Sprowls

The Journal of American Drama and Theatre

Volume 35, Number 2 (Spring 2023)

ISNN 2376-4236

©2023 by Martin E. Segal Theatre Center

How can a traditional practice for Jewish text study inform the dramaturgical analysis of a new work development process? This article is a conversation between Jared Rubin Sprowls and Becca Levy about the playwright/dramaturg relationship in rehearsing a staged reading of Fringe Sects at Arizona State University in the spring of 2022. We were eager to gather in physical space with artists to re-engage with the liveness of our work, a process that had largely been put on hold since the onset of the COVID-19 pandemic.

What began as a peer-reviewed research paper naturally grew into a dramaturgical adaptation of chevruta, a centuries old Rabbinic approach to interpreting Jewish texts. The style of this paper mimics our process of multiple voices in conversation. In chevruta, dialogue is necessary as one voice can’t capture the depth of a text; we can only approach understanding through discussion and interpretation. Through this lens, we push against prioritizing finality (a deadline, production, or publication) which dictates a linear process. Rather, we hold space to return again, offering a process that spans a lifetime as both the people and art deepen and unfold. We share authorship below, identifying the writer above each section. Though our names signify what we initially wrote, through revision, our voices continue to overlap, always in conversation. As we consider how this lens is valuable for new work development, both Jewish and non-Jewish, we invite you to engage in our reflection of Fringe Sects’ script development as a fellow chevruta partner: our voice, your voice, and the text.

Jared

In March 2020, I was finally ready to write my “Jewish play” based on a Buzzfeed article a friend sent to me a year prior: “Finding Kink in God: Inside The World Of Brooklyn Dominatrixes And Their Orthodox Jewish Clients.” [1] This article complicated the stereotype of Jewish sexuality I saw being portrayed on stage and screen: Jews as less sexual and less desirable. Expanding what a Jewish “man,” “woman,” or “relationship” looked like felt important to my own understanding of Jewish queerness and an inquiry I could share with my community. COVID interrupted that plan as Jewish sexuality onstage was no longer an urgent exploration, instead it was the last thing on my mind. What we thought would be a few weeks of mandated isolation became months. As Passover approached, I felt detached from my Jewish identity without the ability to invite friends over for Seder. The holiday traditions, rooted in community, didn’t feel the same with only me and my two roommates skimming through the Haggadah.

In August 2021, I moved to Tempe, Arizona to pursue an MFA in Dramatic Writing. Fear of isolation continued, and I wondered what I’d do for the upcoming High Holidays. Rosh Hashanah felt like an opportunity for a new chapter in the desert, but I wondered if anyone would be there to join me.

Becca

That’s where our Research Methods course comes in; it was my first semester of grad school as well, beginning the MFA program in Theatre for Youth and Community at ASU. I had also just moved to Tempe from Chicago, and much to my delight and surprise the old song “Wherever you go there’s always someone Jewish”[2] proved to be true. I overheard Jared talking about Jewish dominatrixes and had to learn more.

Jared

As I discussed revisions to my research question, I vividly remember Becca leaning over to join the conversation. Another Jewish woman to discuss Jewish womanhood and femininity? Baruch Hashem! On that day, I was paired with Clara, whose Hebrew necklace had sparked conversation a class prior. Marissa would soon ask what we were doing for Rosh Hashanah. She too had overheard the musings of Jewish study and wanted to join. We had all worried that we’d be the only Jew in the program and were relieved to have found each other so quickly.

Becca

Jared and I requested to be paired for the final round of peer review. What was scheduled to be a brief meeting about our papers over coffee became a multi-hour conversation relating our artistry to our values and our values to our Judaism. We intuitively worked as chevruta: a non-hierarchical dyadic practice of Jewish text study rooted in traditional methods going back centuries. A chevruta partnership is a meaningful and holy relationship through which we understand text, and our relationship to text, more fully. The word chevruta comes from the Hebrew root chet, vet, reish, chaver, meaning “friend,” emphasizing that this relationship is between more than peers or colleagues. In fact, it’s not just a relationship between two voices, but three: two people and the text. Scholarly discourse around Fringe Sects was a catalyst for our partnership, while genuine friendship became central to our ongoing collaboration.

Jared was researching about Jewish gender and sexuality while more deeply connecting with Jewish ways of being through his writing.

Jared

Where do the stereotypes, roles, and ideas of Jewish women come from? Who perpetuates them within our community and how does that differ from what we see in the media?

Becca

In my initial notes, I wrote about the importance of discoveries, using this play to reveal Jewish challenges and provide space for healing while weaving the Jewish with the universal–

Jared

Questions and themes that simultaneously drew me into Becca’s research.

Becca

What is the relationship between creativity, identity, and values in Jewish artmaking spaces? Grad school was the opportunity to further explore our embodied knowledge through research and practice.

Jared

Research and practice exist over coffee as much as they exist in conferences and classrooms. I got to know Becca through her research, and I better understood her research by getting to know Becca.

Becca

We spent the next semester together in a graduate Dramaturgy Workshop course. One of our first readings was from Geoffrey Proehl’s Towards a Dramaturgical Sensibility; I sent Jared a text, “Ok so I finally started the reading this morning and tbh I think a dramaturgical sensibility is just simply how Jews read Torah”[3] [4]. I quickly recognized in Proehl’s description of dramaturgical practice a kinship with Jewish ways of thinking, conversing, and analyzing.

Jared

“Isn’t there a Jewish thing about rehearing the Torah and the purpose of that? Helping me connect dramaturgy and Judaism again”[5], I texted Becca as we continued to quip that “dramaturgy is Jewish.” It became our special segment in class where we reflected on how teachings from Jewish synagogue, camp, and school prepared us to analyze text as dramaturgs.

Later that semester, I assembled a team for a staged reading of Fringe Sects at ASU: Marissa as director, Becca as dramaturg, and Clara, Matt (the only other Jew in our MFA program) and Sam (a non-Jewish MFA peer) as actors. The energy of the rehearsal room was immediately alive –

Becca

Is the milk a reference to milk and honey?

Jared

I hadn’t even thought of that.

Becca

What about the Binding of Isaac?

Jared

That sounds like BDSM.

Becca

Our playful yet serious conversations around script development were contagious, or perhaps Jared had just gathered the perfect group for this week-long rehearsal process. We were more than Jewish artists chosen for a Jewish play; we were friends. In our first few months of grad school, we had already spent High Holidays, birthdays, and Chanukah together, discussed art that was important to us, and reflected on the ways our Judaism connected us even when it manifested differently. In fact, the different shades of Judaism were what we celebrated most: the variety of latke recipes, family and community traditions, or the way we pronounced “bimah.”

Questioning, connecting, and respecting the multitude of text interpretations based on our diverse lived experiences were the foundation upon which the script could develop so significantly in such a short amount of time. Reflecting upon the process, it is clear that this ensemble intuitively worked from a place of shared values.

Jared

It was interpretive. It was direct. It was Jewish.

Becca

Jared and I always bring these values into our creative practice. Through this process we affirmed that we practice those values creatively in specifically Jewish ways.

Jared

Although I had been in a new work development space with other Jewish artists, I had never felt that a room was guided by a Jewish way of reading text in the way this process was. Sam’s active participation proved that anyone can engage with text in this way. Not only did this way of working benefit the script, but it was life-giving. I was no longer an isolated writer but an artist in the community.

Becca

Going deeper into the etymology of chevruta, the Hebrew chaver (friend) derives from the Aramaic, chibor, meaning “to bind together.” In this process, chevruta partners’ understanding of text becomes bound together in discussion, creating something entirely new with what is on the page. Below is an example of a text study where a peer and I engaged with the very first Torah portion. The first translation you’ll read is a more standard version and the second is a collaborative translation discovered in shared study. While working with the text, I was drawn to the word “ruach” which translates to “wind” or “spirit” and my partner noticed “pnei” which can mean “surface” or “face.” We excitedly investigated more translations and read the text anew. Together, we uncovered a translation that neither of us would have found on our own.

Hebrew words with multiple meanings are illustrated below in corresponding colors. I invite you to notice what is the same, what is different, and how these changes influence your understanding of the text.

When God created heaven and earth, the earth was chaos and void, with darkness over the surface of the deep and a wind from God fluttering over the surface of the waters. (Genesis 1:1-2)

When The Universe began to create sky and land, the land was without form and void. Behold darkness over the face of the abyss and the spirit of Creation floating over the face of the waters. (Genesis 1:1-2) [6]

Stereotypical depictions of dramaturgy seem so isolating– an image of a lonely scholar with their head in their laptop or a book comes to mind; it’s not so different from the rabbi locked in their study or b’nai mitzvah student up in their room, practicing their Torah portion alone. But these are all misrepresentations of reality. To be Jewish is to congregate. To make theatre is to congregate. In the process of working together we bond with one another and the work binds to the point where it’s sometimes hard to know where one person’s idea ends and another’s begins. Jared and I intuitively did this work with our research papers, with everything we read in Dramaturgy Workshop, and with our collaboration on Fringe Sects.

Jared

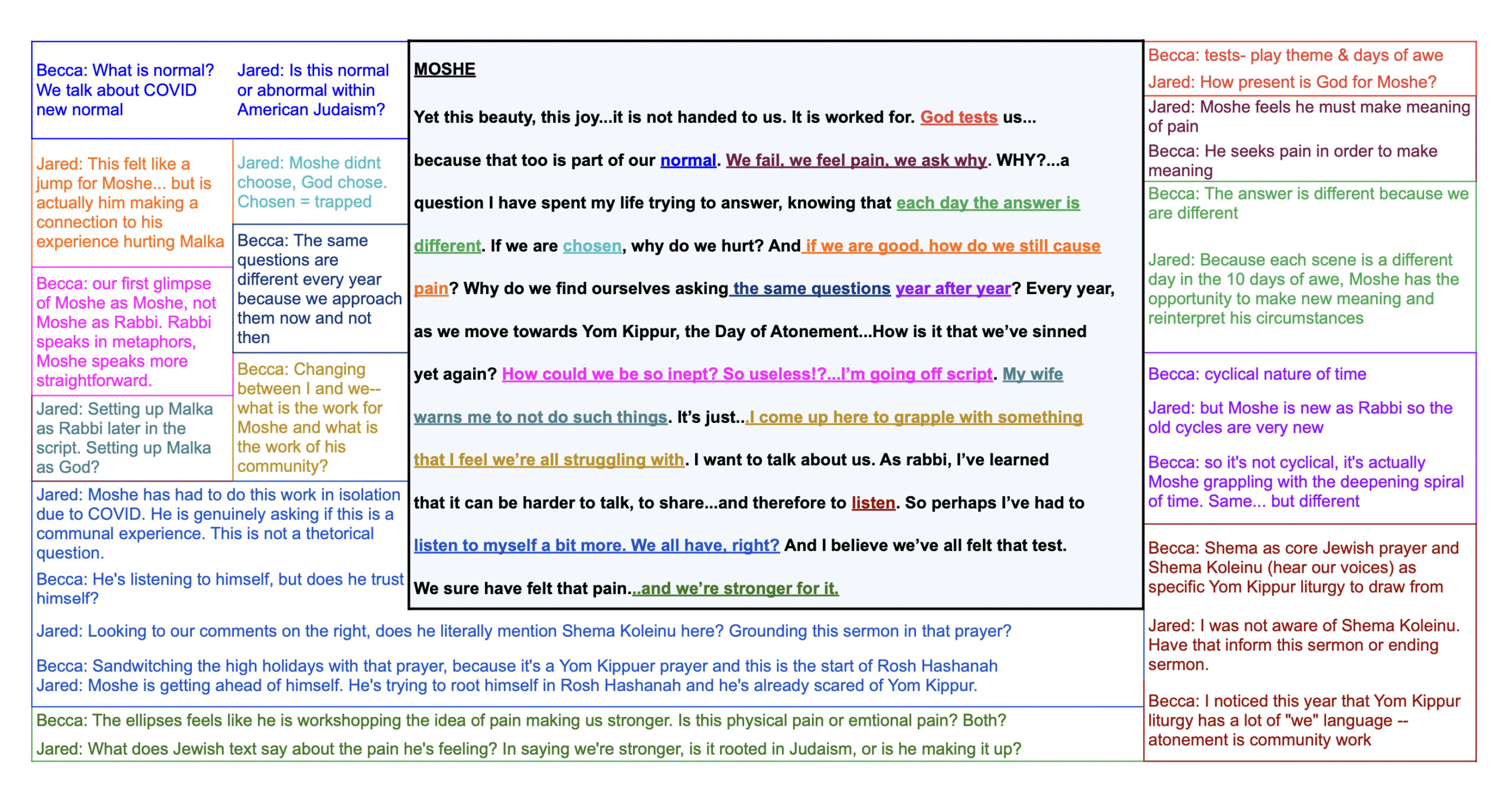

Below is a visual representation of our chevruta-inspired conversations analyzing a paragraph from the opening monologue of the play, Rabbi Moshe’s Rosh Hashanah sermon, which we’ve retroactively formatted in the style of rabbinic commentary of Talmud.

Becca

Rabbi Adina Allen writes, “Like the parchment wound around the Torah handles, our reading of this story is not circular, but spiral. We move along the same axis, but drop in and down, unearthing new meanings in the cracks of our old stories” [7]. This concept of time provides repetition while acknowledging that with repetition comes a new depth of experience in the present. During our collaboration on Fringe Sects, Jared and I trusted each other to continue to drop in and down in the reading and re-reading, writing, and re-writing, talking and re-talking of the script. We built trust and a shared language through cultural understanding, shared values, and unearthing new meanings while the script developed.

The play is set during The Ten Days of Awe, the time between Rosh Hashanah and Yom Kippur, when we’re tasked with Tshuvah. Tshuvah means to “return:” to return to right relationship with one another, the world around us, and ourselves. We return to something old or familiar – an ancient practice, text, or question. We seek to find something new, not in hopes of the perfect answer or action, but to embrace the multiplicity of interpretations and meaning-making as part of the process.

Jared

Even in the process of writing this article, we return again. Remembering text messages we forgot we had sent, making notes for our next stage of development.

Becca

(I still want Jared to add the shehecheyanu into that scene).

Jared

(I will).

Becca

These conversations ground us because there’s always something new to uncover.

Jared

If chevruta is three voices, our process contains even more: playwright, dramaturg, director, cast, characters, script, research, prayer, Torah, and Talmud. If Jewish text, ancient and unchanging, contains such multitudes, we must listen to all possibilities as a new work finds its voice. To give a script agency is to understand that it will never actually be finished…

Becca

…but it is always where it’s supposed to be.

Jared

Jewish values tell us that we too are not finished and that growth is a lifelong process.

Becca

As the spiral continues to deepen, may we delight in moments of synchronicity and express gratitude for moments of divergence.

Jared & Becca

As this article concludes, we invite you to bring yourself into our chevruta practice. In doing so you join us in community and together we begin again.

Becca Levy is an arts educator and theatre artist who facilitates educational programs and theatrical productions that center community, celebrate culture, and foster creativity for people of all ages. Becca worked as a teaching artist, arts program manager, and stage manager in Chicago after earning her BFA in Stage Management from Western Michigan University. Currently studying for an MFA in Theatre for Youth and Community at Arizona State University, her praxis explores the relationship between creativity and values, drawing from many years of work and play in Jewish arts programming and theatre teaching artistry. www.beccaglevy.com

Jared Rubin Sprowls is a Chicago-based playwright currently in Tempe, Arizona pursuing an MFA in Dramatic Writing at Arizona State University. His work has been produced Off-Broadway through the Araca Project, as well as at Northwestern University and the Skokie Theatre. He is a 2018 O’Neill NPC Semi-finalist and has been a part of Available Light’s Next Stage Initiative, the New Coordinates’ Writers’ Room 6.0, and Jackalope Theatre’s Playwrights Lab. He is a project-based staff member with Crossroads Antiracism Organizing and Training. He holds a B.A. with Honors in Theatre from Northwestern University.

[1] https://www.buzzfeed.com/hannahfrishberg/dominatrixes-orthodox-jewish-haredi-kink-bdsm-brooklyn

[2] Milder, Rabbi Larry. “Wherever You Go There’s Always Someone Jewish.”

[3] Levy, Becca. Text message to Jared Sprowls. 23 Jan. 2022.

[4] Proehl, Goeffrey. Towards a Dramaturgical Sensibility: Landscape and Journey. Madison:

Fairleigh Dickinson University Press, 2008.

[5] Sprowls, Jared. Text message to Becca Levy. 30 Jan. 2022.

[6] This text study and my learnings on chevruta come from Becca’s time with the Jewish Studio Project. She has been participating in the Jewish Studio Process, a Jewish art-making and text study practice, with them since May 2020 and is currently part of their Creative Facilitator Training Cohort.

[7] Allen, Rabbi Adina. “The Kernel of the Yet-to-Come.” My Jewish Learning, 21 Oct. 2022,

https://www.myjewishlearning.com/article/the-kernel-of-the-yet-to-come/amp/.